Greetings from Wauwatosa, Wisconsin. Nan and Scout and I are on a road trip back home for a week or so. We left Grand Junction on Friday afternoon and spent the night with Nan's sister Sue and brother-in-law Jack in Boulder. Scout got to meet his "cousin" Buddy, Sue and Jack's one-year-old golden retriever. They spent most of the time play-fighting and chasing each other in the backyard. After getting the car serviced in Denver the next morning, we drove all day on Interstate 80 to reach Grand Island, Nebraska, the halfway point of the trip. We stayed at an old Howard Johnson's because they allowed dogs and then hit the road bright and early the next day.

Greetings from Wauwatosa, Wisconsin. Nan and Scout and I are on a road trip back home for a week or so. We left Grand Junction on Friday afternoon and spent the night with Nan's sister Sue and brother-in-law Jack in Boulder. Scout got to meet his "cousin" Buddy, Sue and Jack's one-year-old golden retriever. They spent most of the time play-fighting and chasing each other in the backyard. After getting the car serviced in Denver the next morning, we drove all day on Interstate 80 to reach Grand Island, Nebraska, the halfway point of the trip. We stayed at an old Howard Johnson's because they allowed dogs and then hit the road bright and early the next day. I spent the first nine years of my life in Iowa City, Iowa and hadn't been back there in almost twenty years, so we pulled off I-80 to do a quick driving tour before continuing on. As we exited the interstate and drove down 1st Avenue, we could see that the damage from the recent flooding of the Iowa River had been severe. Many of the stores and restaurants along the river were badly damaged and closed for business.

I spent the first nine years of my life in Iowa City, Iowa and hadn't been back there in almost twenty years, so we pulled off I-80 to do a quick driving tour before continuing on. As we exited the interstate and drove down 1st Avenue, we could see that the damage from the recent flooding of the Iowa River had been severe. Many of the stores and restaurants along the river were badly damaged and closed for business.Our first stop was City Park, a big fixture in my childhood. My siblings and I learned to swim at the pool there during summer vacations. The first photo shows Scout in the grass near the pool and the second shows the two of us walking next to it. The high-dive you can see is the first one I ever went off, at age five with my "Guppies" swimming classmates.

Our next stop was my first school, Mark Twain Elementary. Like everything from childhood, it looked much smaller than I remembered. I peered into the windows of my kindergarten classroom and was surprised at how little it had changed from my days there forty-five years ago.

Our next stop was my first school, Mark Twain Elementary. Like everything from childhood, it looked much smaller than I remembered. I peered into the windows of my kindergarten classroom and was surprised at how little it had changed from my days there forty-five years ago. Our final stop was the home we lived in before moving to Wisconsin back in 1967. The single-story house at 2103 Hollywood Blvd. looked tiny, especially compared to the large trees in the front yard. When we lived there, the trees were about as thick as my wrist and provided little shade. Now the entire neighborhood is filled with mature shade trees, creating a completely different atmosphere from the sun-baked one of my memories.

Our final stop was the home we lived in before moving to Wisconsin back in 1967. The single-story house at 2103 Hollywood Blvd. looked tiny, especially compared to the large trees in the front yard. When we lived there, the trees were about as thick as my wrist and provided little shade. Now the entire neighborhood is filled with mature shade trees, creating a completely different atmosphere from the sun-baked one of my memories.

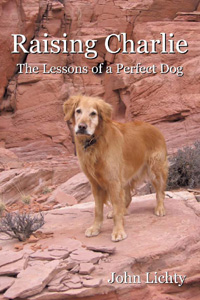

Raising Charlie: The Lessons of a Perfect Dog

Raising Charlie: The Lessons of a Perfect Dog