Many scholars have concentrated on the insanity of Ahab's obsession. To me, that was merely the device that drove the plot. The greater story is the one of man's place in the universe and his perception of that place. The whalers are routinely successful in their hunt until they finally encounter Moby-Dick at the book's climax. Their incredible hubris is revealed in the absolute destruction the whale wreaks upon their world, killing everyone but Ishmael, the narrator who survives to tell the tale.

The message is that man is but a small component in this universe and that the universe, despite man's feelings to the contrary, is largely indifferent to him. Much of this message is contained within the following paragraph, about two-thirds of the way through the book, when one of the cabin boys, who has joined the chase with the whalers for just his second time, jumps out of the boat in fear:

But it so happened, that those boats, without seeing Pip, suddenly spying whales close to them on one side, turned, and gave chase; and Stubb's boat was now so far away, and he and all his crew so intent upon his fish, that Pip's ringed horizon began to expand around him miserably. By the merest chance the ship itself at last rescued him; but from that hour the little negro went about the deck an idiot; such, at least, they said he was. The sea had jeeringly kept his finite body up, but drowned the infinite of his soul. Not drowned entirely, though. Rather carried down alive to wondrous depths, where strange shapes of the unwarped primal world glided to and fro before his passive eyes; and the miser-merman, Wisdom, revealed his hoarded heaps; and among the joyous, heartless, ever-juvenile eternities, Pip saw the multitudinous, God-omnipresent, coral insects, that out of the firmament of waters heaved the colossal orbs. He saw God's foot upon the treadle of the loom, and spoke it; and therefore his shipmates called him mad. So man's insanity is heaven's sense; and wandering from all mortal reason, man comes at last to that celestial thought, which, to reason, is absurd and frantic; and weal or woe, feels them uncompromised, indifferent as his God.Pip's brush with death exposed to him the truth of man's situation and changed him forever in the eyes of his shipmates. "Insane" is the label others place upon those whose perception does not match their own.

It is apparent why this book created such a sensation when it was published more than 150 years ago. The language and imagery are advanced, even by modern standards. It is a difficult but rewarding book and well worth the time it takes to work through it.

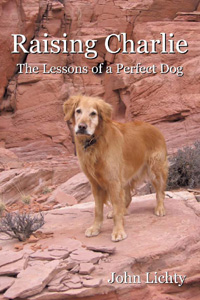

Raising Charlie: The Lessons of a Perfect Dog

Raising Charlie: The Lessons of a Perfect Dog

1 comment:

one starving musician came by to say: that is one classic I havent read yet. nice blog entry.

j.e.

Post a Comment