For as long as he could remember, Sam had wanted to run away. Many children go through a phase of trying to escape from their overbearing parents, sometimes making it only as far as the end of the driveway, but Sam was different: he wanted to escape from everybody.

This desire of Sam’s may have been the result of a personality quirk from earliest childhood. Instead of developing from the stage of unconscious self to the stage of conscious self and then settling there, Sam continued on to a stage of self-conscious self. He was acutely aware not only of himself but also of how he was perceived by other people, and he was extremely sensitive to their acceptance or rejection.

School was especially difficult for Sam. His self-consciousness made him appear meek, and his classmates often took advantage, teasing and bullying. Sam was baffled by this treatment because he did not see himself as being different from other children. If they could understand things as he did, why would they ever utter an unkind word or treat others poorly? So Sam dreamed of running away.

In second grade, the alphabetical ordering of the desks put him at the back of his row and gave him his first escape opportunity. When his teacher wasn’t looking, Sam would slowly back his desk away from the one in front of his. Over the course of several days, he eventually reached the back wall of the classroom, next to a table on which an experiment with butterflies and cocoons was underway. From his new vantage point, he could see everything happening in the room, like a guard up in a tower, watchful and isolated. He believed his teacher either wasn’t paying attention or didn’t care. But then one day, out of the corner of his eye, he saw a giant moth emerge from one of the cocoons, and he let out a yelp of surprise. His teacher was more angry at him for disturbing the class than she was pleased that the experiment had been successful, and she made him keep his desk in line with the others from then on.

Fourth grade, in a new school and in a new town, presented new challenges. Many of the other children had known each other since kindergarten, so Sam was even more of an outsider than usual. During one of his first recesses, some of his classmates decided that they would force him to kiss his classmate, Mary. A group of the boys grabbed his arms and dragged him kicking and screaming to where a group of the girls was holding Mary. When their lips were just inches apart, Sam broke free and ran toward an elevated corner of the playground. A classmate, Jim, grabbed his arm to stop him, and Sam wheeled around and punched him hard in the stomach, knocking the wind out of him. From the high corner, he turned to face his attackers, but the bell rang to end recess and everyone filed back inside. By the time Sam returned to his classroom, his teacher already knew about the punch, and she escorted him downstairs to the principal’s office. On the way, he tried to explain himself, but she would have none of it. At the principal’s office, he was told to phone home, but he explained that his mother and father were at work. He would have gone home anyway, to escape from school, but that was not an option. There was nothing to be done but to give Sam a stern talking-to and then escort him back to the classroom, where his classmates did not conceal the scorn they felt for him.

Two years later, as Sam was entering sixth grade, he received an invitation in the mail to join a local Boy Scout troop. He saw it as an opportunity to go camping, an activity he had dreamed about as an escape into the wilderness but one in which his parents would never participate. The troop’s first camp-out took place within weeks of his joining, and he slept on the ground and cooked over a wood fire for the very first time. As he lay on his back in his tent, he knew that the camping life was the life for him.

The following summer, he went with his troop to Boy Scout camp, a week-long stay at a permanent camp that offered merit badge classes, canoe trips and other advanced activities. He saw during sign-up that there would be an overnight survival trip and he signed up for it immediately, even though none of his troop mates did.

On the morning of the trip, Sam arrived early and took a seat in the grass at the meeting place. He had only his pack, a sleeping bag, a ground cloth, a pocketknife and an empty peach can, as the rules for the trip specified, and his brand-new hiking boots, which kids called “waffle stompers.” The next boy to show up was Kevin, a tough kid with bad teeth and a beat-up felt hat. Sam tried to make friends, but Kevin would only say, “Nice shoes, Nimrod,” so he gave up trying. Butterfly, the trip’s instructor, showed up and Sam directed his attention toward learning as much as he could from him. After a brief orientation and equipment check, the scouts started out down a trail that Sam had not known existed. Along the way, Butterfly pointed out edible plants and had the boys sample them. Sam was pleasantly surprised that many of the plants he encountered in the woods could be eaten, but he imagined it would take an awful lot of them to make up a meal. They came to a small stream, and Butterfly amazed the boys by getting down on his hands and knees and drinking directly from it. He explained, as he stood up and wiped his mouth, that the waters that ran through these woods were very clean, clean enough even for trout to live in. Sam imagined catching a trout to round out his meal of edible plants. The thought made him hungry. They had not been allowed to pack any food, and it was now past lunch time.

The trail followed the stream down to where it emptied into a swampy pond. Butterfly waded out into the muddy water and pulled up some cat tails by their roots. He brought them back to shore and had the boys sample the root shoots. They weren’t too bad, Sam thought, a little like tasteless carrots. Butterfly explained that the cat tails would make up a large portion of their dinner that night, so they should find and cut up enough shoots to fill their peach cans. So much for Sam’s new boots.

The scouts continued down the trail, squishing in their muddy boots, until they reached an area at the far end of the pond that looked like it had been torn up by bulldozers. Butterfly explained that this would be their camp for the night. He arbitrarily broke the boys up into groups, and Sam was disappointed to see that he was grouped with Kevin and another boy. Each group was assigned a campsite, which was nothing more than a large excavated hole in the ground, with a fire pit at the bottom of it. There was also a puddle at the bottom of Sam’s group’s hole, and a frog was swimming in it. Kevin whipped off his pack, jumped into the hole and snagged the frog out of the puddle. Sam felt a little sick as he watched Kevin bend the frog’s head down until its neck snapped. “I’ll be eating good tonight,” Kevin exulted as he pulled out his pocketknife to butcher the frog. Sam looked to the other boy, who was smiling at Kevin’s antics but not saying anything.

Sam found a flat spot above the hole and set down his gear. He plucked several fern fronds to make a mattress and then laid down his ground cloth and sleeping bag. He was proud of his little bed until Kevin came over. “Nice bed, Nimrod.” Other boys were wandering down to the pond to get water, so Sam joined them to get away from Kevin. Through the clear water, Sam could see that the pond’s bottom was covered with small snails. When he pointed them out, another boy reached into the water for one, crushed its shell with his fingers and sucked out the insides. The boy grimaced but swallowed. “They taste like muddy snot,” he said. Sam decided he would try to make do with his cat tail shoots and added water to his peach can full of them.

Shortly after he returned to the campsite, Butterfly came by to help Sam’s group get a fire started. The boys had not been allowed to bring matches, but Butterfly had a flint stick, which he used to scrape sparks into some dry pine duff. It ignited immediately, and the boys raced around the edges of the campsite for sticks and logs to keep the fire burning. Before long, they had a regular bonfire burning at the bottom of their hole. Kevin insisted that they gather all the wood they could find before it got dark and that they set up a watch schedule to keep the fire burning all night long.

Sam set his peach can full of water and cat tail shoots on a flat rock next to the fire to heat up. Kevin had skewered his frog on a stick and had it roasting at the edge of the flames. The other boy was heating up a can full of snails. Maybe they’ll taste better cooked, Sam thought, but he doubted it. As the water in his can heated up, it turned purple. Butterfly had told them that this was an indication that the shoots were ready to eat. Sam stabbed a piece with his pocketknife and put it in his mouth. The outside was warm and chewy, but the inside was still cool and crunchy and tasteless. Sam ate enough to fill his empty stomach and washed it down with the leftover water. He tried not to think of Kevin and the other boy eating their frog and snails.

When it got dark, Kevin announced that he would take the first watch. He warned that the fire had better not go out later, while he was asleep. “I’m looking at you, Nimrod.” Sam crawled inside his sleeping bag and lay on his side watching the fire. The next thing he knew, the other boy was shaking him awake for his watch. Sam added more logs and poked at the fire for a while. Then he sat on his sleeping bag at the edge of the hole, watched the fire and tried to stay awake. He drifted off for a while and then woke up suddenly, still sitting upright. He had no idea what time it was. None of the boys had wristwatches, so the idea of a set watch schedule suddenly seemed completely stupid. Sam got up to stoke the fire back to Kevin’s standards and then went to wake him up. Kevin came awake thrashing like he was being attacked, but he settled down quickly and got up to tend the fire. Sam crawled back in his sleeping bag and rolled with his back to the fire. “Sleep tight, Nimrod.”

He wasn’t sure if he was dreaming it at first, but Sam heard voices in the night, Kevin and another boy talking and laughing. He came awake enough to see a hulking kid from another campsite standing next to the fire with Kevin before he drifted off to sleep again. He dreamed that he was suffocating, unable to take a breath and unable to move. He awoke in disbelief to find the hulking kid standing on his chest with both feet. Sam let out a strangled yell and rolled out from under the boy’s weight. Kevin and the boy laughed as Sam coughed and tried to catch his breath. He couldn’t believe that someone would suffocate a person in his sleep as a joke. He wanted to run screaming into the woods to get away from them, but it was dark and he didn’t want to get lost. He curled up on his side in his sleeping bag and willed it to be morning. “That was a good one, Nimrod.”

These childhood experiences did little to enamor Sam to the human race, and he grew more and more withdrawn. Instead of playing with friends after school, he would spend his late afternoons in the school library, where he befriended the librarian, Miss Angus. She supported his love of reading, not suspecting that Sam had grown to prefer books to people, and introduced him to many works he would never have discovered on his own.

One afternoon in the library, Sam found a copy of My Side of the Mountain by Jean George. The cover featured a photo from the Walt Disney movie based on the book. It showed a boy hiding behind a boulder with a falcon perched on his gloved hand. Sam flipped through the book and noticed that it was illustrated with black-and-white line drawings of the boy and his falcon. He flipped back to the beginning and started reading. The story was about a boy named Sam Griggs who dreamed of running away to live in the woods. Sam was immediately awestruck. It was as if he were reading the story of his own life, or at least of the life he imagined. He and Sam Griggs even had the same first name. It must be some kind of a sign, he thought. He checked the book out of the library and raced home to read it.

Sam Griggs ran away from New York City to live on his family’s ancestral farmstead in the Catskills. The farm had long since fallen into ruin, but Sam Griggs endeavored to live off the land, eating only what he could hunt or gather. He made his home in the hollow trunk of an enormous hemlock tree, and he captured a young peregrine falcon and trained it to hunt for him.

To Sam, it seemed the perfect life, living alone in the wilderness, and he began to think about where he could live a similar life. He had read many of Jack London’s stories and so imagined the Canadian frontier as a likely place. He pored over detailed topographic maps at the library and decided that one of the small rivers that fed into James Bay, the small bay at the southern end of Hudson Bay, would be isolated enough without being so far north that the winters would be endless. Sam spent his free time daydreaming about what his life there would be like, building a canoe and using it to fish the rivers and lakes, hunting for game with an old flintlock rifle, maybe running a trap line and selling the furs to get needed supplies.

Years passed, but the daydreams never materialized into an actual plan. Sam still thought about running away, especially when his self-consciousness interfered with his social relationships, but he was no longer sure that Canada was where he wanted to go. In the spring of his junior year in high school, Sam went on a group ski trip to Utah and was introduced to the Wasatch Mountains. The trip’s organizers had planned for a non-skiing day of horseback riding, and the group rode sturdy little winter-coated horses up into the mountains for a picnic lunch. Seeing the burbling brooks, the blooming aspen trees and the abundant wildlife of the mountains renewed Sam’s desire to run away to the wilderness and convinced him that the Utah mountains were where he wanted to be.

When he returned home, Sam again pored over maps, this time looking for the perfect Utah location. He chanced upon the Uintah Mountains, to the east of the Wasatch Mountains, and discovered that they are the only east-west oriented mountain range in the whole of the Rocky Mountain region. He located the highest point in the Uintahs, Kings Peak, and noted that it was also the highest point in Utah. He had recently seen the movie Jeremiah Johnson, and he imagined himself living a mountain man’s existence on the warm, south-facing slopes of Kings Peak.

Unlike his daydreams of Canada, Sam’s thoughts of Utah quickly formed into a plan. He wrote up elaborate equipment lists and started accumulating what he could afford. He read extensively on wilderness survival techniques and studied the flora and fauna of Utah. He mapped the best access points and plotted their routes. And when he felt he was as prepared as he could be, he couldn’t make himself go. It wasn’t that he was afraid. His desire to escape outweighed his fears, but still, there was something he couldn’t pin down holding him back. Was he anticipating a final catastrophic event in his life that would give him the necessary push? He wasn’t sure. And so he waited.

A few years later, during the summer between his sophomore and junior years in college, Sam’s family took a road trip to Keystone, Colorado. Sam saw the trip as an opportunity to take a trip of his own, a solo overnight backpacking adventure. Despite all his dreams of being alone in the wilderness, he had never actually experienced it. So he put together a knapsack of his survival equipment and began checking his maps. Shortly after their arrival in Keystone, Sam noticed a mountain, Independence Peak, which overlooked the resort and could be reached from a trail that started at the base of the ski area. He had his parents drop him off there one sunny morning late in their trip.

Sam felt a surge of adrenaline as he started out alone up the trail. It was really more of a summer access road that switched back and forth up the ski trails, but all that mattered to Sam was that he was alone in the Colorado wilderness. He hiked steadily, stopping only occasionally for a drink from his water bottle. He crested a rise and saw a mule deer only twenty yards away. The deer wasn’t startled by Sam’s presence, so he continued to watch it until it wandered away. By noon, he had reached tree line and found an old fire ring that marked a good place to camp. He took off his pack and sat down on a rock to eat his lunch. From his high vantage point, Sam could see the resort far below and the sky to the west. Clouds were forming, but they didn’t look threatening. He turned to look up at the summit of Independence Peak. It didn’t look too far away, maybe another hour or so of hiking. Since he planned to camp where he was that night, he didn’t see any reason to carry his pack up to the summit and back. He hung it in a tree and set out for the peak. Away from the shelter of the trees, the wind blew hard and cold. Sam put up the hood on his jacket and concentrated on hiking carefully up the rocks and trackless tundra to the final approach ridge. He looked up periodically to check his progress and was surprised each time to see that he seemed no closer to the summit.

It started to snow, blowing sideways in the high wind and stinging Sam’s face. He stopped and held up his bare hand to catch some of it, and he saw that it was more like tiny pieces of hail than snow. No wonder it stung. He adjusted his hood and looked up to the peak. It was almost obscured by hail and scudding clouds. He turned and looked back down the way he had come and calculated that he was only halfway to the top from where he had left his pack. His reasons for climbing the peak were escaping him and with them, his desire to continue. He took one more long look at the summit he would not reach and then turned to go.

Back below tree line, there was protection from the wind and hail. After locating his pack, Sam walked in widening circles around the fire ring, collecting sticks to make a campfire. When he had enough to last until bedtime, he went to work building a small fire. When it was going steadily, he unpacked his sleeping bag and ground cloth from his pack and made himself a bed a little ways upwind of the fire. He unpacked a small pot and the freeze-dried meal he had brought for dinner. He filled the pot with water from his water bottle, knocked the fire down to coals and then placed the pot on top of the coals to boil. When the water was boiling, he poured it into the aluminum pouch of his freeze-dried meal, stirred the contents with a spoon and set it aside to reconstitute. He stoked the fire back to flames, walked to the edge of his camp and looked to the west. The clouds had cleared and the sun was almost down. Far below, he could see lights twinkling in the resort. Sam felt very far removed from civilization for the first time in his life and very much alone. He wasn’t sure how it made him feel. He turned and looked at his camp, glowing in the firelight, and was heartened to see how the light of a campfire can define a small personal space in an otherwise vast wilderness.

Sam checked on his dinner and found it ready to eat. He sat on a rock with the pouch on his knee and spooned the food into his mouth. It wasn’t bad tasting. And it was hot and plentiful. He ate until the pouch was empty and then set it aside. The fire had died down, and it was now fully dark. Sam looked up at the moonless night and saw so many stars that he couldn’t pick out familiar constellations. He watched the sky until a shooting star sliced past, then he got up, stoked the fire one last time to push back the dark, got into his sleeping bag and fell immediately to sleep.

He wasn’t sure if he was dreaming it at first, but Sam heard a buzzing sound in the night. He came awake enough to see a hummingbird hovering above the smoldering remains of his campfire before he drifted off to sleep again. He dreamed that he was suffocating, unable to take a breath and unable to move. He awoke to find himself alone in the dark. There was no hulking kid standing on his chest this time. He lay on his back, coughing and trying to catch his breath. As his breathing returned to normal, he stared up at the stars and thought about his life. He thought about the cruel and senseless things that people had done to him. He thought about how much he hated those people in return. And he came to understand that despite all his feelings to the contrary, he was very much a member of the human race and he would never be able to escape it. His dreams of running away would only ever be realized through brief camping trips like this one he was on. He felt an old burden slowly lifting from his mind. He was resigned but at peace.

Sam awoke at dawn the next morning, packed up his equipment, checked to make sure the campfire was out, and then hiked down the mountain to rejoin civilization.

This blog is an account of the pursuit of a dream, to sail around the world. It is named after the sailboat that will fulfill that dream one day, Whispering Jesse. If you share the dream, please join me and we'll take the journey together.

For Charlie and Scout

For Charlie and Scout

About Me

- John Lichty

- Savannah,

Georgia, USA

"Go confidently in the direction of your dreams. Live the life you have imagined." --Henry David Thoreau

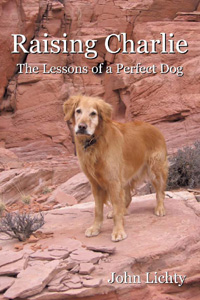

Raising Charlie: The Lessons of a Perfect Dog by John Lichty

Raising Charlie: The Lessons of a Perfect Dog by John Lichty

Blog Archive

Followers

Recommended Links

- ATN Sailing Equipment

- ActiveCaptain

- BoatU.S.

- Coconut Grove Sailing Club

- Doyle Sails - Fort Lauderdale

- El Milagro Marina

- John Kretschmer Sailing

- John Vigor's Blog

- Leap Notes

- Noonsite.com

- Notes From Paradise

- Pam Wall, Cruising Consultant

- Practical Sailor

- Project Bluesphere

- Sail Makai

- So Many Beaches

- Windfinder

Wednesday, February 29, 2012

Monday, February 13, 2012

Crested Butte

Last weekend, I took a ski trip with friends Bryce and Brian to Crested Butte and Telluride. I can't remember the last time I went on a "stag" ski trip, but I was eager to go on this one because I would get to ski at Crested Butte for the first time.

Bryce had stayed once before at a remote lodge called The Inn at Arrowhead, located near Cimarron, Colorado and more or less centrally located for both ski resorts, so I booked it for both Friday and Saturday nights. It turned out that we were the only guests for the weekend, except for groups of snowmobilers who stopped for breakfast and lunch at the Inn's excellent restaurant, but host James was most welcoming. He even kept the bar open past its ten o'clock closing time for us.

Colorado is having a mild winter. Whole sections of Crested Butte were closed due to lack of snow, and the snow they did have reminded me of the "Hometown Ice" I grew up skiing back in Wisconsin. It was slick and fast, and it never really softened up, even though it was a bright sunny day, because the temperature refused to rise out of the twenties. Bryce had skied at Crested Butte before, so he directed us to some good intermediate terrain to start with and then we spent the rest of the day exploring, taking a ride on each open chairlift at least once.

After skiing, we headed into town for appetizers and drinks at the legendary Wooden Nickel. We were the only customers when we arrived, which we blamed on the relatively poor ski conditions. The ski mountain hadn't been very crowded either; we never waited more than a minute or two in any lift lines, and most of the people in line were local season-pass holders.

Back at the Inn, we ate steak dinners and then watched "Hot Tub Time Machine" on Bryce's portable DVD player. It's kind of a ski movie, or at least it has some skiing scenes, but mostly it's a crazy comedy (K-Val!). By the time it was over, it was past time for bed.

We stopped by my friend Kevin's house in Montrose the next morning to pick him up on our way to ski Telluride. The ski conditions there were no better than at Crested Butte, and it was a gray, cloudy day, so the visibility wasn't very good either. The only highlight was skiing a run in Revelation Bowl, but it is above treeline so there was nothing to give relief against the snow in the flat light. It was purely "ski by feel."

At last count, there are twenty-six ski resorts in Colorado. Counting Crested Butte, I have skied at sixteen of them. After being locked into skiing in the Aspen area for twenty years with a ski pass commitment, it is liberating to try new ski resorts. I have made it a casual goal to try to ski every one in the state eventually. Liking climbing the 14ers, it's a great way to see our great state.

Bryce had stayed once before at a remote lodge called The Inn at Arrowhead, located near Cimarron, Colorado and more or less centrally located for both ski resorts, so I booked it for both Friday and Saturday nights. It turned out that we were the only guests for the weekend, except for groups of snowmobilers who stopped for breakfast and lunch at the Inn's excellent restaurant, but host James was most welcoming. He even kept the bar open past its ten o'clock closing time for us.

Colorado is having a mild winter. Whole sections of Crested Butte were closed due to lack of snow, and the snow they did have reminded me of the "Hometown Ice" I grew up skiing back in Wisconsin. It was slick and fast, and it never really softened up, even though it was a bright sunny day, because the temperature refused to rise out of the twenties. Bryce had skied at Crested Butte before, so he directed us to some good intermediate terrain to start with and then we spent the rest of the day exploring, taking a ride on each open chairlift at least once.

After skiing, we headed into town for appetizers and drinks at the legendary Wooden Nickel. We were the only customers when we arrived, which we blamed on the relatively poor ski conditions. The ski mountain hadn't been very crowded either; we never waited more than a minute or two in any lift lines, and most of the people in line were local season-pass holders.

Back at the Inn, we ate steak dinners and then watched "Hot Tub Time Machine" on Bryce's portable DVD player. It's kind of a ski movie, or at least it has some skiing scenes, but mostly it's a crazy comedy (K-Val!). By the time it was over, it was past time for bed.

We stopped by my friend Kevin's house in Montrose the next morning to pick him up on our way to ski Telluride. The ski conditions there were no better than at Crested Butte, and it was a gray, cloudy day, so the visibility wasn't very good either. The only highlight was skiing a run in Revelation Bowl, but it is above treeline so there was nothing to give relief against the snow in the flat light. It was purely "ski by feel."

At last count, there are twenty-six ski resorts in Colorado. Counting Crested Butte, I have skied at sixteen of them. After being locked into skiing in the Aspen area for twenty years with a ski pass commitment, it is liberating to try new ski resorts. I have made it a casual goal to try to ski every one in the state eventually. Liking climbing the 14ers, it's a great way to see our great state.

Wednesday, February 8, 2012

Headlights

When I was younger, I was the kind of person who would flash his headlights at people driving at night without their headlights turned on. I was also the kind of person who would turn off people's headlights in parking lots if I saw that their car doors were unlocked. I figured I was doing those people a favor, saving some from a traffic ticket and others from a dead battery.

I don't do those things anymore. Now when I see people driving without headlights or forgetting to turn them off, I shake my head and move on. I mind my own business. It's not that I don't care. It's that my way of looking at things has changed. Too many times, people have flashed their headlights back at me in anger, or I have set off a car alarm. The satisfaction of having helped someone in some small way now seems less valuable to me than seeing firsthand that actions have consequences. Life's experiences have provided me with many good lessons, and I trust that they will do the same for others.

I don't do those things anymore. Now when I see people driving without headlights or forgetting to turn them off, I shake my head and move on. I mind my own business. It's not that I don't care. It's that my way of looking at things has changed. Too many times, people have flashed their headlights back at me in anger, or I have set off a car alarm. The satisfaction of having helped someone in some small way now seems less valuable to me than seeing firsthand that actions have consequences. Life's experiences have provided me with many good lessons, and I trust that they will do the same for others.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)