When I was a kid in the sixties, my friends and I were crazy about the NASA space program. Astronauts were our heroes, and my friend, Gary Benskin, wanted to be one when he grew up. He even built a model of the Gemini 4 space capsule, complete with astronaut Ed White floating outside it for the first American space walk.

Back then, during the Cold War, when the United States was competing with Russia in the "space race," every launch was a huge deal. My teacher would wheel a TV into our classroom so we could watch the live telecasts from Cape Canaveral. We studied astronomy and built "scale" models of the solar system. Even The Weekly Reader featured articles about space. I remember one story that included a photo of a test rocket that would be able to land on an airport runway instead of splashing down in the ocean. That, of course, was the space shuttle, which has dominated the space program since the last manned mission to the moon in December 1972 by Apollo 17 but is destined to be sidelined later this year.

I sometimes ask people what they think is the pinnacle of human history. Most don't have an answer, but when I tell them that for me, it is the Apollo 11 moon landing on July 20, 1969, they usually agree. Unfortunately, it has been all downhill since then. Sure, we have sent probes out to explore our solar system and beyond, and we have built some impressive space stations, but we have not revisited the moon in almost forty years. When I saw 2001: A Space Odyssey in 1968 ("Thank you, Arthur C. Clarke"), I imagined that the future would be just like that: shuttles whisking people between the earth and space, scientists colonizing the moon, and astronauts exploring deep space with the help of intelligent robots. Almost none of that has happened, and for me, that is the greatest unrealized dream and deepest disappointment of my life.

Now the Obama administration is scrapping the Constellation program, which would have put us back on the moon by 2020. The implication is that we would be better off putting our resources into planning a manned mission to Mars, but NASA authorities say that there are too many unknowns to be able to meet that same timeline, or any timeline for that matter, without the research and development that would have come out of the Constellation program. So the space program will be essentially operating without a long-range plan. For people my age, who had hoped to see man walk on Mars in our lifetimes, who had even dreamed of going there themselves one day, this is terrible news.

This blog is an account of the pursuit of a dream, to sail around the world. It is named after the sailboat that will fulfill that dream one day, Whispering Jesse. If you share the dream, please join me and we'll take the journey together.

For Charlie and Scout

For Charlie and Scout

About Me

- John Lichty

- Savannah,

Georgia, USA

"Go confidently in the direction of your dreams. Live the life you have imagined." --Henry David Thoreau

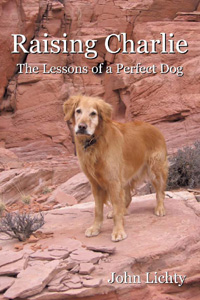

Raising Charlie: The Lessons of a Perfect Dog by John Lichty

Raising Charlie: The Lessons of a Perfect Dog by John Lichty

Blog Archive

Followers

Recommended Links

- ATN Sailing Equipment

- ActiveCaptain

- BoatU.S.

- Coconut Grove Sailing Club

- Doyle Sails - Fort Lauderdale

- El Milagro Marina

- John Kretschmer Sailing

- John Vigor's Blog

- Leap Notes

- Noonsite.com

- Notes From Paradise

- Pam Wall, Cruising Consultant

- Practical Sailor

- Project Bluesphere

- Sail Makai

- So Many Beaches

- Windfinder

Friday, February 26, 2010

Tuesday, February 16, 2010

Mathew Brady’s Assistant (A Fictional History)

Alexander Gardner, a twenty-nine-year-old Scotsman from Glasgow, attended Prince Albert and Queen Victoria’s Great Exhibition in London’s Hyde Park in May, 1851. There he viewed an exhibit of photographs by the American photographer, Mathew Brady, and was inspired to apply his interest in chemistry to the relatively new science of photography.

When Alexander returned home, he began to experiment with the collodion, or wet-plate, process of taking and developing photographs, which resulted in prints that were far superior in quality to those created using the more common daguerreotype process.

Wanting to impress his wife, Margaret, with his newfound talent, Alexander set up his camera and tripod in the parlor of their home on a sunny Saturday afternoon for a family portrait. The shutter had not yet been invented, so exposure was controlled by removing and then replacing the lens cap. This made it impossible for Alexander to both take a photograph and be a subject in it at the same time. Thus, his first family photograph was of Margaret and their two children alone.

It was bedtime before Alexander emerged from his improvised darkroom with a finished print of the family photograph in his hands. He hurried up the stairs to the bedroom to show it to Margaret, who was seated at her dressing table brushing her hair. She saw him in the mirror, turned to see the photograph, and gasped.

“What is it, dear?” Alexander asked in alarm.

“Well, I recognize the children, but who is that woman standing with them?”

“Why, that’s you, of course.”

“But it can’t be! I look nothing like that!” She turned back to the mirror and pointed at her reflection. “That is how I look! Your picture is completely wrong!”

Thinking quickly, Alexander held the photograph in front of his chest and moved next to where Margaret was sitting. Catching her eye in the mirror, he asked, “Is this better?”

Margaret shifted her focus to the reflection of the photograph and narrowed her eyes in concentration. “Yes. It is. Now it looks right.” She picked up her hairbrush and resumed brushing her hair. “I never want to see that awful picture again.”

Deeply disappointed, Alexander lay awake in bed long into the night trying to think of a possible solution to this unexpected problem. His wife had never seen an image of herself that was not a reflection and so believed the reflection to be her true image. But the camera did not take reflections; it took only true images. As dawn began to lighten the edges of the window shades, he believed he had found an answer.

Alexander went through his family’s Sunday morning routine with no hint of what he was planning. At breakfast, when the children asked about the previous day’s photograph, he met Margaret’s eyes and said, “It didn’t turn out well, so I destroyed it. We’ll try again later today, after lunch. I promise.” Margaret raised her eyebrows as if to ask what he could possibly have in mind but said nothing. They finished breakfast, dressed in their finest clothes, and walked to church.

Later, while Margaret prepared lunch in the kitchen and the children played outside, Alexander quietly got up from reading his newspaper in the parlor, carried his camera and tripod up to the bedroom, and then returned to his reading.

As they finished lunch, the children reminded their father about his promise to take another photograph. Alexander responded as if he had forgotten, “Yes, that’s right. I did promise, didn’t I?” He pushed away from the table and stood up. “Well, let’s go try our luck.”

He led his family into the parlor. “Father, where is the camera?” the younger child asked.

“I thought we would try something different,” he replied. “I moved it up to the bedroom.”

The children giggled as he led them and Margaret up the stairs. In the bedroom, the camera and tripod stood facing Margaret’s dressing table. Her chair was positioned to the right facing the camera, across from a short stool, with the dressing table’s full-length mirror between the two seats. Alexander escorted Margaret to her chair and placed the younger child on her lap. He posed the older child on the stool and then walked to the back of the camera. He had prepared a wet plate earlier, so all he needed to do was to adjust the focus. As he looked through his viewfinder, he noticed the perplexed expressions on his family’s faces and smiled.

“All right. Now, Margaret, you and I are going to switch places.” He walked over and plucked the child from her lap. Margaret stood up and walked uncertainly to the camera as Alexander sat and positioned the child on his lap.

“That’s it, dear,” Alexander said. “But instead of standing behind the camera, step to the side of it. There! Do you see it?”

Margaret looked at the scene before her and did indeed see it. Her image was reflected in the mirror as though she were standing with her family seated in front of her.

Alexander directed her and the children, “Margaret, all you need to do is reach out with your right hand and remove the lens cap, count to ten, and then replace it. Children, you must remain absolutely still.”

Margaret moved her hand toward the camera and noticed her reflected hand moving in the mirror. With her fingers touching the lens cap, her reflected hand appeared to be resting behind Alexander’s shoulder. She moved her left hand to position it so it looked like it was resting on her older child’s back. The effect was so real that she couldn’t help but smile. Her family smiled back to see her so delighted. Without moving, she removed the lens cap, counted to ten, and then replaced it. Alexander let out an animated sigh of relief, and the children laughed. Margaret laughed as well, with love for her clever husband.

When it was developed and printed, the family gathered to inspect the new photograph. Margaret appeared to be exactly centered in the frame of her dressing table mirror, with her family seated before her. If one overlooked the fact that had she actually been standing there, there would have been a noticeable reflection of her back in the mirror, then the trick was a success, except for a very slight blurring of her arm behind Alexander’s shoulder.

“It’s perfect, dear,” said Margaret. “I love it.”

Within five years, Alexander Gardner and his family had immigrated to the United States, where his expertise in using the collodion process to create large portraits, called Imperial photographs, was in great demand. Alexander contacted Mathew Brady in Washington, D.C., and was promptly hired as his assistant and gallery manager. When the Civil War began, Brady undertook to make a photographic record of it, and Alexander became Brady’s chief field photographer, taking many of the most famous battlefield photographs, including the controversial Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter. He also took the last photographs of President Abraham Lincoln, four days before his assassination, and photographed the conspirators after their arrest and at their execution.

When Alexander returned home, he began to experiment with the collodion, or wet-plate, process of taking and developing photographs, which resulted in prints that were far superior in quality to those created using the more common daguerreotype process.

Wanting to impress his wife, Margaret, with his newfound talent, Alexander set up his camera and tripod in the parlor of their home on a sunny Saturday afternoon for a family portrait. The shutter had not yet been invented, so exposure was controlled by removing and then replacing the lens cap. This made it impossible for Alexander to both take a photograph and be a subject in it at the same time. Thus, his first family photograph was of Margaret and their two children alone.

It was bedtime before Alexander emerged from his improvised darkroom with a finished print of the family photograph in his hands. He hurried up the stairs to the bedroom to show it to Margaret, who was seated at her dressing table brushing her hair. She saw him in the mirror, turned to see the photograph, and gasped.

“What is it, dear?” Alexander asked in alarm.

“Well, I recognize the children, but who is that woman standing with them?”

“Why, that’s you, of course.”

“But it can’t be! I look nothing like that!” She turned back to the mirror and pointed at her reflection. “That is how I look! Your picture is completely wrong!”

Thinking quickly, Alexander held the photograph in front of his chest and moved next to where Margaret was sitting. Catching her eye in the mirror, he asked, “Is this better?”

Margaret shifted her focus to the reflection of the photograph and narrowed her eyes in concentration. “Yes. It is. Now it looks right.” She picked up her hairbrush and resumed brushing her hair. “I never want to see that awful picture again.”

Deeply disappointed, Alexander lay awake in bed long into the night trying to think of a possible solution to this unexpected problem. His wife had never seen an image of herself that was not a reflection and so believed the reflection to be her true image. But the camera did not take reflections; it took only true images. As dawn began to lighten the edges of the window shades, he believed he had found an answer.

Alexander went through his family’s Sunday morning routine with no hint of what he was planning. At breakfast, when the children asked about the previous day’s photograph, he met Margaret’s eyes and said, “It didn’t turn out well, so I destroyed it. We’ll try again later today, after lunch. I promise.” Margaret raised her eyebrows as if to ask what he could possibly have in mind but said nothing. They finished breakfast, dressed in their finest clothes, and walked to church.

Later, while Margaret prepared lunch in the kitchen and the children played outside, Alexander quietly got up from reading his newspaper in the parlor, carried his camera and tripod up to the bedroom, and then returned to his reading.

As they finished lunch, the children reminded their father about his promise to take another photograph. Alexander responded as if he had forgotten, “Yes, that’s right. I did promise, didn’t I?” He pushed away from the table and stood up. “Well, let’s go try our luck.”

He led his family into the parlor. “Father, where is the camera?” the younger child asked.

“I thought we would try something different,” he replied. “I moved it up to the bedroom.”

The children giggled as he led them and Margaret up the stairs. In the bedroom, the camera and tripod stood facing Margaret’s dressing table. Her chair was positioned to the right facing the camera, across from a short stool, with the dressing table’s full-length mirror between the two seats. Alexander escorted Margaret to her chair and placed the younger child on her lap. He posed the older child on the stool and then walked to the back of the camera. He had prepared a wet plate earlier, so all he needed to do was to adjust the focus. As he looked through his viewfinder, he noticed the perplexed expressions on his family’s faces and smiled.

“All right. Now, Margaret, you and I are going to switch places.” He walked over and plucked the child from her lap. Margaret stood up and walked uncertainly to the camera as Alexander sat and positioned the child on his lap.

“That’s it, dear,” Alexander said. “But instead of standing behind the camera, step to the side of it. There! Do you see it?”

Margaret looked at the scene before her and did indeed see it. Her image was reflected in the mirror as though she were standing with her family seated in front of her.

Alexander directed her and the children, “Margaret, all you need to do is reach out with your right hand and remove the lens cap, count to ten, and then replace it. Children, you must remain absolutely still.”

Margaret moved her hand toward the camera and noticed her reflected hand moving in the mirror. With her fingers touching the lens cap, her reflected hand appeared to be resting behind Alexander’s shoulder. She moved her left hand to position it so it looked like it was resting on her older child’s back. The effect was so real that she couldn’t help but smile. Her family smiled back to see her so delighted. Without moving, she removed the lens cap, counted to ten, and then replaced it. Alexander let out an animated sigh of relief, and the children laughed. Margaret laughed as well, with love for her clever husband.

When it was developed and printed, the family gathered to inspect the new photograph. Margaret appeared to be exactly centered in the frame of her dressing table mirror, with her family seated before her. If one overlooked the fact that had she actually been standing there, there would have been a noticeable reflection of her back in the mirror, then the trick was a success, except for a very slight blurring of her arm behind Alexander’s shoulder.

“It’s perfect, dear,” said Margaret. “I love it.”

Within five years, Alexander Gardner and his family had immigrated to the United States, where his expertise in using the collodion process to create large portraits, called Imperial photographs, was in great demand. Alexander contacted Mathew Brady in Washington, D.C., and was promptly hired as his assistant and gallery manager. When the Civil War began, Brady undertook to make a photographic record of it, and Alexander became Brady’s chief field photographer, taking many of the most famous battlefield photographs, including the controversial Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter. He also took the last photographs of President Abraham Lincoln, four days before his assassination, and photographed the conspirators after their arrest and at their execution.

Wednesday, February 10, 2010

"Plain Sailing"

Shortly after our Spanish Virgin Islands sailing trip last April, fellow crewmember and well-known author Dallas Murphy emailed me a copy of his manuscript-in-progress, Plain Sailing: Learning to See Like a Sailor, A Sail Trim Manual for New Sailors. I took my time working through it, and I was impressed. It was packed with information I have never read anywhere else. It filled some gaps in my understanding of sail performance and reignited my desire to experiment with achieving perfect sail trim.

I have searched the Internet since then for signs that Plain Sailing had been published so I could buy a copy, but there have been no references to it. On a whim, I emailed Dallas recently with the idea of helping him get the book published if that was what it would take. He appreciated my offer but informed me that the book had been commissioned by a friend who owned a one-man publishing business, so he was committed to following through with him.

Well, it was worth a try. When Plain Sailing is finally published, it will be a reference that every sailor would find useful. Keep an eye out for it.

I have searched the Internet since then for signs that Plain Sailing had been published so I could buy a copy, but there have been no references to it. On a whim, I emailed Dallas recently with the idea of helping him get the book published if that was what it would take. He appreciated my offer but informed me that the book had been commissioned by a friend who owned a one-man publishing business, so he was committed to following through with him.

Well, it was worth a try. When Plain Sailing is finally published, it will be a reference that every sailor would find useful. Keep an eye out for it.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)