When Mike woke me up shortly before the end of his three-to-six watch, he said, “John, you should come up and look at this.” I was in the cockpit moments later, staring at the wall of darkness off our stern. Even in the pre-dawn light, it looked ominous. I checked the wind. It was still blowing lightly out of the south, enough for us to have the mainsail up in conjunction with the diesel engine to keep us moving southwest toward Savannah.

We were far enough offshore that the VHF weather channel would not come in clearly. Neither Mike nor Kurt, who had joined us in the cockpit, could remember any storm forecasts. It’s just a squall, I thought, like the ones that blow quickly through the Caribbean at this time of year.

Within minutes, the wind had clocked around one hundred eighty degrees and piped up to almost twenty knots. The sail started flapping and I told Mike to steer into the wind to avoid an accidental jibe. The sea lumped up in a hurry, with swells approaching eight to ten feet. Now we were pointed directly into the wind and the sail was flapping like crazy. I had Mike fall slightly off the wind to keep the sail full and the bow pointed into the waves. Cold rain fell like BBs, mixing with the warm spray coming off the waves. As the boat crested, I looked for signs of lightness beneath the dark clouds, but there was only blackness from sea to sky. The sun had come up, but it was not penetrating the clouds anywhere that we could see.

We took turns at the helm as each of us went below to put on rain gear. As time went by, we commented on how much distance we were losing toward our destination. Still there was no lightness below the clouds. Waves crashed over the boat and drove water through the leaky hatches and into the cabin. Everything below was getting soaked. Anything that was not secured had been pitched onto the floor. We could hear the cooler crashing around, but nobody wanted to go below to secure it. We had each thrown up by now, and Mike admitted to having thrown up twice. Going below would only trigger another bout.

After two hours of fore-reaching, we decided it was pointless to believe we would eventually sail out of the storm’s leeward edge. This was no squall. No, not at all! We were about thirty miles away from Charleston Harbor, and I suggested that we try to sail there instead of continuing on to Savannah. I offered to pay for a hotel room if we made it. Thoughts of hot showers, good food and warm beds immediately focused our efforts. To reach Charleston, we would need to turn around and resume a southwesterly heading. But the mainsail would need to come down first.

Mike volunteered to go forward and manage the sail as Kurt lowered it. With the boat pitching wildly, Kurt and I did not envy him. Mike moved carefully to the mast as I steered the boat directly into the wind, causing the sail to flap dangerously. Kurt released the cam on the halyard and it went flying through its brake but hung up on a slipknot when the sail was only halfway down. Mike threw his body over the boom and lashed a sail tie around what he could. I punched the autopilot’s button and ran down the companionway stairs to grab a marlinspike for Kurt. Mike returned to the cockpit and worked with Kurt to untie the knot, then went forward again, but not before putting on a harness and clipping its leash to a lifeline. He had come close to falling overboard the first time and was taking no chances. He managed to get the sail tied well enough and returned to the cockpit.

I turned the boat around and aimed for the sea buoy that marks the beginning of the shipping lane entrance to Charleston Harbor. If the boat had been pitching before, now it was rolling dramatically from side to side as we surfed up and down the faces of huge waves at an angle that was the shortest path to our destination but also uncomfortably close to beam on. We wedged ourselves into corners of the cockpit and trusted the boat to fully right itself before the next wave surged beneath us.

Through it all, the trusty diesel engine kept up a steady two thousand RPMs, moving us to safety at six knots. By late morning, we had spotted the sea buoy, about fifteen miles offshore, and knew we were on course for Charleston Harbor. The red and green buoys that followed were up to a mile apart and difficult to locate. We scanned with the binoculars at wave crests to spot them and adjusted course accordingly. More than an hour later, I spotted the immense Arthur J. Ravenel Bridge through the mist, our first sight of land in almost two days. The sea turned slowly from blue to green, and the waves died down to a point where the boat was no longer surfing but merely lumbering.

I checked the signal strength on my cell phone, then called my parents in Savannah to let them know we were safe but that we would be ending the trip in Charleston. They had not been aware of the bad weather but agreed to drive up and get us the next day.

The stars and stripes that fly above Fort Sumter came into view. I thought about the fort’s historical significance as the place where the Civil War began and tried to imagine cannonballs hurtling toward ships sailing in the same waters we were now motoring through. It was a sobering thought. We continued past the fort and followed the buoys up the Ashley River to City Marina. By three o’clock, we were safely secured in a slip, where Whispering Jesse will stay until Mike and I return to sail the remaining distance to Savannah next week.

This blog is an account of the pursuit of a dream, to sail around the world. It is named after the sailboat that will fulfill that dream one day, Whispering Jesse. If you share the dream, please join me and we'll take the journey together.

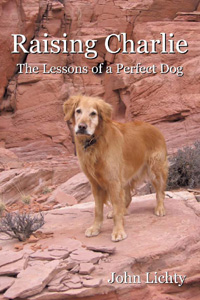

For Charlie and Scout

For Charlie and Scout

About Me

- John Lichty

- Savannah,

Georgia, USA

"Go confidently in the direction of your dreams. Live the life you have imagined." --Henry David Thoreau

Raising Charlie: The Lessons of a Perfect Dog by John Lichty

Raising Charlie: The Lessons of a Perfect Dog by John Lichty

Blog Archive

-

▼

2011

(62)

-

▼

October

(9)

- Google Map of the Trip from Charleston to Savannah

- Check-in/OK message from Whispering Jesse SPOT Mes...

- Check-in/OK message from Whispering Jesse SPOT Mes...

- Check-in/OK message from Whispering Jesse SPOT Mes...

- Check-in/OK message from Whispering Jesse SPOT Mes...

- Check-in/OK message from Whispering Jesse SPOT Mes...

- Check-in/OK message from Whispering Jesse SPOT Mes...

- Just a Squall? No, not at All!

- Photos from the Sailing Trip

-

▼

October

(9)

Followers

Recommended Links

- ATN Sailing Equipment

- ActiveCaptain

- BoatU.S.

- Coconut Grove Sailing Club

- Doyle Sails - Fort Lauderdale

- El Milagro Marina

- John Kretschmer Sailing

- John Vigor's Blog

- Leap Notes

- Noonsite.com

- Notes From Paradise

- Pam Wall, Cruising Consultant

- Practical Sailor

- Project Bluesphere

- Sail Makai

- So Many Beaches

- Windfinder

Saturday, October 8, 2011

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment